CXXI: Bridging the C++ and C# worlds.

The Mono runtime engine has many language interoperability features but has never had a strong story to interop with C++.

Thanks to the work of Alex Corrado, Andreia Gaita and Zoltan Varga, this is about to change.

The short story is that the new CXXI technology allows C#/.NET developers to:

- Easily consume existing C++ classes from C# or any other .NET language

- Instantiate C++ objects from C#

- Invoke C++ methods in C++ classes from C# code

- Invoke C++ inline methods from C# code (provided your library is compiled with -fkeep-inline-functions or that you provide a surrogate library)

- Subclass C++ classes from C#

- Override C++ methods with C# methods

- Expose instances of C++ classes or mixed C++/C# classes to both C# code and C++ as if they were native code.

CXXI is the result of two summers of work from Google's Summer of Code towards improving the interoperability of Mono with the C++ language.

The Alternatives

This section is merely a refresher of of the underlying technologies for interoperability supported by Mono and how developers coped with C++ and C# interoperability in the past. You can skip it if you want to get to how to get started with CXXI.

As a reminder, Mono provides a number of interoperability bridges, mostly inherited from the ECMA standard. These bridges include:

- The bi-directional "Platform Invoke" technology (P/Invoke) which allows managed code (C#) to call methods in native libraries as well as support for native libraries to call back into managed code.

- COM Interop which allows Mono code to transparently call C or C++ code defined in native libraries as long as the code in the native libraries follows a few COM conventions [1].

- A general interceptor technology that can be used to intercept method invocations on objects.

When it came to getting C# to consume C++ objects the choices were far from great. For example, consider a sample C++ class that you wanted to consume from C#:

class MessageLogger {

public:

MessageLogger (const char *domain);

void LogMessage (const char *msg);

}

One option to expose the above to C# would be to wrap the Demo class in a COM object. This might work for some high-level objects, but it is a fairly repetitive exercise and also one that is devoid of any fun. You can see how this looks like in the COM Interop page.

The other option was to produce a C file that was C callable, and invoke those C methods. For the above constructor and method you would end up with something like this in C:

/* bridge.cpp, compile into bridge.so */

MessageLogger *Construct_MessageLogger (const char *msg)

{

return new MessageLogger (msg);

}

void LogMessage (MessageLogger *logger, const char *msg)

{

logger->LogMessage (msg);

}

And your C# bridge, like this:

class MessageLogger {

IntPtr handle;

[DllImport ("bridge")]

extern static IntPtr Construct_MessageLogger (string msg);

public MessageLogger (string msg)

{

handle = Construct_MessageLogger (msg);

}

[DllImport ("bridge")]

extern static void LogMessage (IntPtr handle, string msg);

public void LogMessage (string msg)

{

LogMessage (handle, msg);

}

}

This gets tedious very quickly.

Our PhyreEngine# binding was a C# binding to Sony's PhyreEngine C++ API. The code got very tedious, so we built a poor man's code generator for it.

To make things worse, the above does not even support overriding C++ classes with C# methods. Doing so would require a whole load of manual code, special cases and callbacks. The code quickly becomes very hard to maintain (as we found out ourselves with PhyreEngine).

This is what drove the motivation to build CXXI.

[1] The conventions that allow Mono to call unmanaged code via its COM interface are simple: a standard vtable layout, the implementation of the Add, Release and QueryInterface methods and using a well defined set of types that are marshaled between managed code and the COM world.

How CXXI Works

Accessing C++ methods poses several challenges. Here is a summary of the components that play a major role in CXXI:

- Object Layout: this is the binary layout of the object in memory. This will vary from platform to platform.

- VTable Layout: this is the binary layout that the C++ compiler will use for a given class based on the base classes and their virtual methods.

- Mangled names: non-virtual methods do not enter an object vtable, instead these methods are merely turned into regular C functions. The name of the C functions is computed based on the return type and the parameter types of the method. These vary from compiler to compiler.

For example, given this C++ class definition, with its corresponding implementation:

class Widget {

public:

void SetVisible (bool visible);

virtual void Layout ();

virtual void Draw ();

};

class Label : public Widget {

public:

void SetText (const char *text);

const char *GetText ();

};

The C++ compiler on my system will generate the following mangled names for the SetVisble, Layout, Draw, SetText and GetText methods:

__ZN6Widget10SetVisibleEb __ZN6Widget6LayoutEv __ZN6Widget4DrawEv __ZN5Label7SetTextEPKc __ZN5Label7GetTextEv

The following C++ code:

Label *l = new Label ();

l->SetText ("foo");

l->Draw ();

Is roughly compiled into this (rendered as C code):

Label *l = (Label *) malloc (sizeof (Label)); ZN5LabelC1Ev (l); // Mangled name for the Label's constructor _ZN5Label7SetTextEPKc (l, "foo"); // This one calls draw (l->vtable [METHOD_PTR_SIZE*2])();

For CXXI to support these scenarios, it needs to know the exact layout for the vtable, to know where each method lives and it needs to know how to access a given method based on their mangled name.

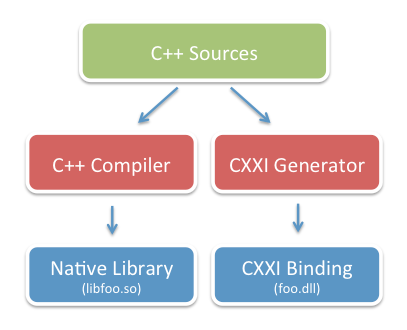

The following chart explains shows how a native C++ library is exposed to C# or other .NET languages:

Your C++ source code is compiled twice. Once with the native C++ compiler to generate your native library, and once with the CXXI toolchain.

Technically, CXXI only needs the header files for your C++ project, and only the header files for the APIs that you are interested in wrapping. This means that you can create bindings for C++ libraries that you do not have the source code to, but have its header files.

The CXXI toolchain produces a .NET library that you can consume from C# or other .NET languages. This library exposes a C# class that has the following properties:

- When you instantiate the C# class, it actually instantiates the underlying C++ class.

- The resulting class can be used as the base class for other C# classes. Any methods flagged as virtual can be overwritten from C#.

- Supports C++ multiple inheritance: The generated C# classes expose a number of cast operators that you can use to access the different C++ base classes.

- Overwritten methods can call use the "base" C# keyword to invoke the base class implementation of the given method in C++.

- You can override any of the virtual methods from classes that support multiple inheritance.

- A convenience constructor is also provided if you want to instantiate a C# peer for an existing C++ instance that you surfaced through some other mean.

This is pure gold.

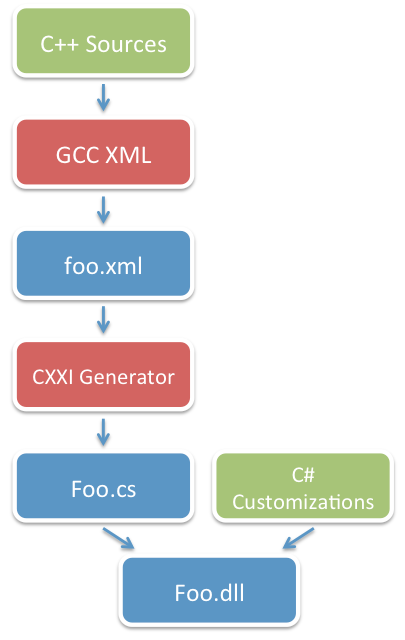

The CXXI pipeline in turn is made up of three

components, as shown in the diagram on the right.

The CXXI pipeline in turn is made up of three

components, as shown in the diagram on the right.

The GCC-XML compiler is used to parse your source code and extract the vtable layout information. The generated XML information is then processed by the CXXI tooling to generate a set of partial C# classes that contain the bridge code to integrate with C++.

This is then combined with any customization code that you might want to add (for example, you can add some overloads to improve the API, add a ToString() implementation, add some async front-ends or dynamic helper methods).

The result is the managed assembly that interfaces with the native static library.

It is important to note that the resulting assembly (Foo.dll) does not encode the actual in-memory layout of the fields in an object. Instead, the CXXI binder determines based on the ABI being used what the layout rules for the object are. This means that the Foo.dll is compiled only once and could be used across multiple platforms that have different rules for laying out the fields in memory.

Demos

The code on GitHub contains various test cases as well as a couple of examples. One of the samples is a minimal binding to the Qt stack.

Future Work

CXXI is not finished, but it is a strong foundation to drastically improve the interoperability between .NET managed languages and C++.

Currently CXXI achieves all of its work at runtime by using System.Reflection.Emit to generate the bridges on demand. This is useful as it can dynamically detect the ABI used by a C++ compiler.

One of the projects that we are interested in doing is to add support for static compilation, this would allow PS3 and iPhone users to use this technology. It would mean that the resulting library would be tied to the platform on which the CXXI tooling was used.

CXXI currently implements support for the GCC ABI, and has some early support for the MSVC ABI. Support for other compiler ABIs as well as for completing the MSVC ABI is something that we would like help with.

Currently CXXI only supports deleting objects that were instantiated from managed code. Other objects are assumed to be owned by the unmanaged world. Support for the delete operator is something that would be useful.

We also want to better document the pipeline, the runtime APIs and improve the binding.

Posted on 19 Dec 2011

Blog Search

Archive

- 2024

Apr Jun - 2020

Mar Aug Sep - 2018

Jan Feb Apr May Dec - 2016

Jan Feb Jul Sep - 2014

Jan Apr May Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2012

Feb Mar Apr Aug Sep Oct Nov - 2010

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2008

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2006

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2004

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2002

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Dec

- 2022

Apr - 2019

Mar Apr - 2017

Jan Nov Dec - 2015

Jan Jul Aug Sep Oct Dec - 2013

Feb Mar Apr Jun Aug Oct - 2011

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2009

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2007

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2005

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2003

Jan Feb Mar Apr Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2001

Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec