TLS 1.2 Comes to Mono: Update

Update to the Update: See Nov 20th, 2017 Update for further updates.

Short version: the master branch of Mono now has support for TLS 1.2 out of the box. This means that SslStream now uses TLS 1.2, and uses of HttpWebRequest for HTTPS endpoints also uses TLS 1.2 on the desktop.

This brings TLS 1.2 to Mono on Unix/Linux in addition to Xamarin.{Mac,iOS,tvOS} which were already enabled to use TLS 1.2 via the native Apple TLS stack.

To use, install your fresh version of Mono, and then either

run the

In Detail

The new version of Mono now embeds Google's Boring SSL as the TLS implementation to use.

Last year, you might remember that we completed a C# implementation of TLS 1.2. But we were afraid of releasing a TLS stack that had not been audited, that might contain exploitable holes, and that we did not have the cryptographic chops to ensure that the implementation was bullet proof.

So we decided that rather than ship a brand new TLS implementation we would use a TLS implementation that had been audited and was under active development.

So we picked Boring TLS, which is Google's fork of OpenSSL. This is the stack that powers Android and Google Chrome so we felt more comfortable using this implementation than a brand new implementation.

Linux Distributions

We are considering adding a --with-openssl-cert-directory= option to the configure script so that Linux distributions that package Mono could pass a directory that contains trusted root certificates in the format expected by OpenSSL.

Let us discuss the details in the [email protected]

Posted on 30 Sep 2016

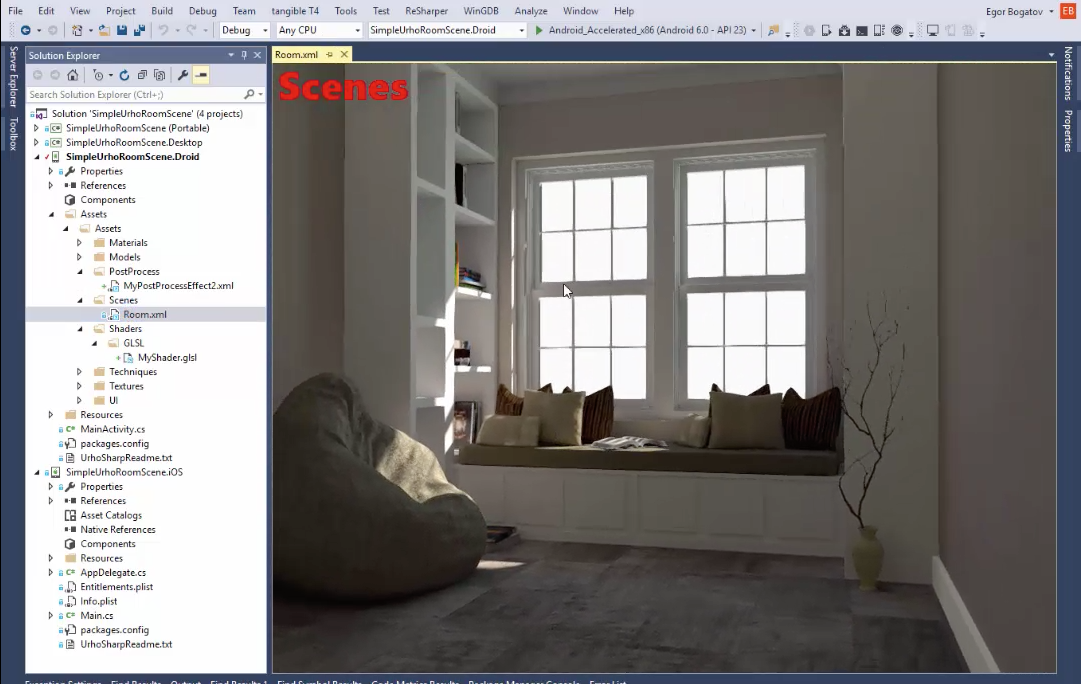

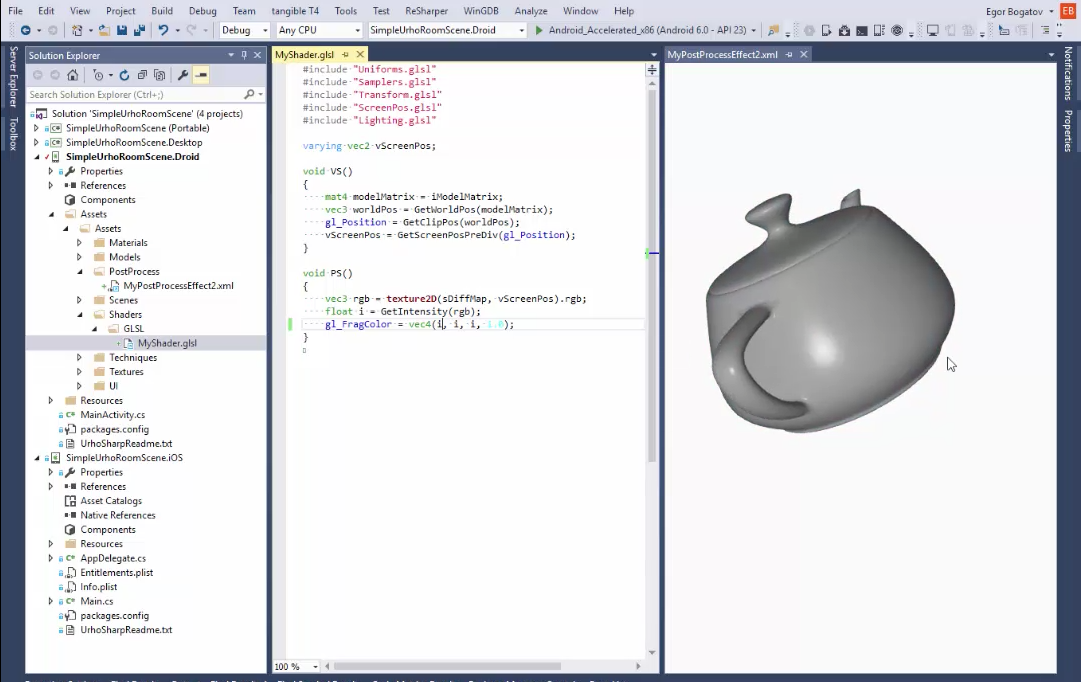

Asset Previewer

Mobile developers are working with all kinds of graphics assets and until now, to preview them, we would use an external tool to browse them.

We have developed a plug-in for both Visual Studio and Xamarin Studio that will provide live previews of various assets right into the IDE. It works particularly well for UrhoSharp projects.

The previewer can display in the IDE previews of the

following asset types.

- Static Models (*.mdl files)

- Materials, Skyboxes, Textures (*.dds)

- Animations (*.ani)

- 2D and 3D Particles (*.pex)

- Urho Prefabs (*.xml if the XML is an Urho Prefab)

- Scenes (*.xml if the XML is an Urho Scene)

- SDF Fonts (*.sdf)

- Post-process effects (*.xml if the XML is an Urho RenderPath)

- Urho UI layouts (*.xml if the XML is an Urho UI).

For Visual Studio, just download the previwer from the Visual Studio Gallery.

For Xamarin Studio, go to Xamarin Studio > Add-ins go to the "Gallery" tab, and search for "Graphics asset previewer" and install.

Posted on 28 Jul 2016

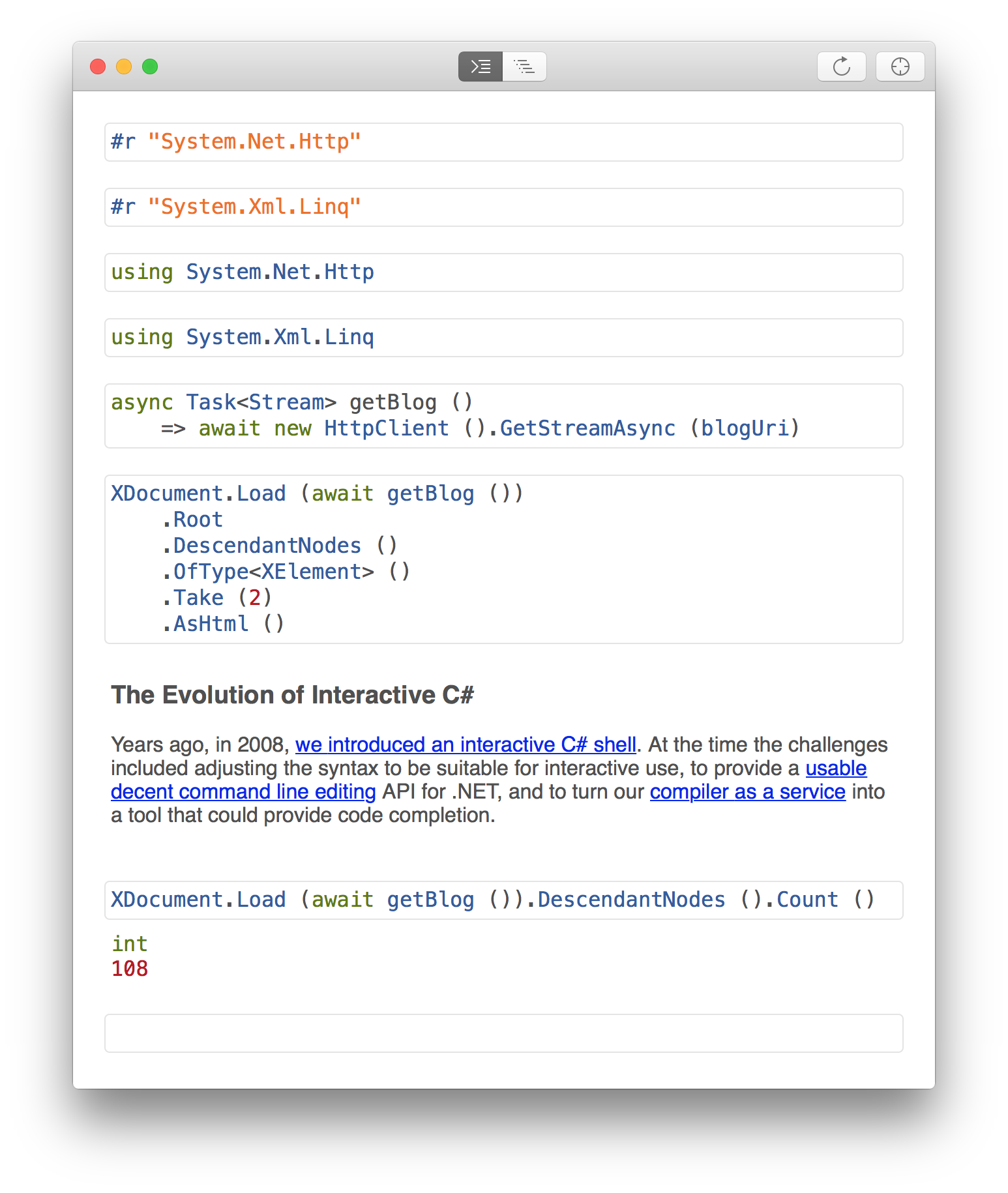

The Evolution of Interactive C#

The Early Days

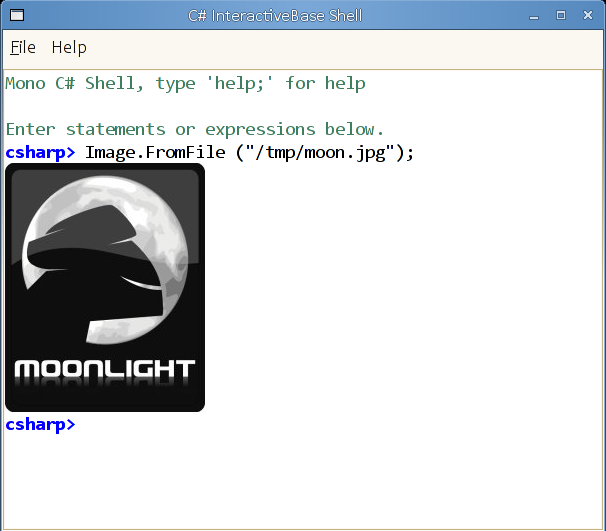

Years ago, in 2008 we introduced an interactive C# shell, at the time a challenge was to adjust the syntax to be suitable for interactive use, to provide a usable decent command line editing API for .NET and to turn our compiler as a service into a tool that could provide code completion.

A few months later, we added a UI shell for this on Linux and used Gtk's text widget to add support for embedding rich content into the responses. It was able to render images inline with the responses:

This was inspired at the time by the work that Owen Taylor at Red Hat had done on Re-interact. You can still watch a screencast of what it looked like.

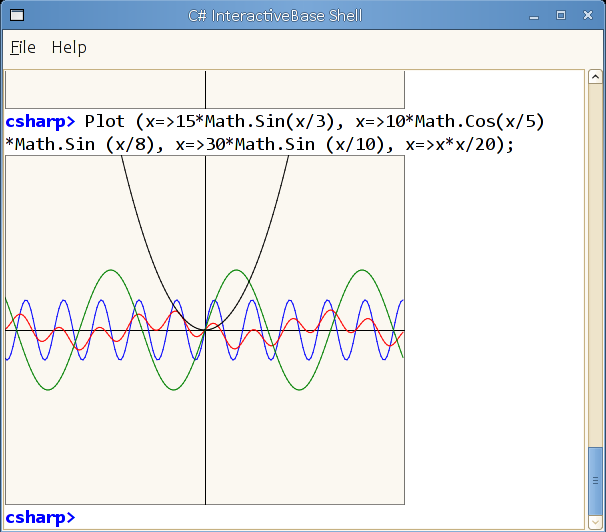

Like Owen, I added a plot command:

At the time, Re-interact took some ideas from IPython and it seems like they are both inspired to some extent by Mathematica's interactive window.

Re-interact in particular introduced a brilliant idea, which was that users could go back in history, edit the previous expressions and the entire buffer would be re-evaluated. This idea lives on in Apple's Playgrounds for Swift.

In the meantime, the IPython project grew and they added one of my favorite features: it was now possible to blend text, explanations and code into workbooks. You can see a sample of this here. For years, I have desired an IPython for C#.

The Xamarin Years

In the meantime, at Xamarin, we experimented with the idea of bringing sometehing like Re-interact/Playgrounds to Xamarin Studio and we shipped Sketches:

But while these were interesting for trying out ideas and learning C#, they are not very useful for day to day work. We found that what our developers needed was a full C# REPL that was connected to the application they were running on, so they could experiment with their UI live. This is when we introduced Xamarin's Inspector. We took the existing engine and changed the way you interacted with C#.

The inspector was originally planned as a debugging aid, one that you could use to attach to a live Android/iOS/WPF process and use to examine:

We wrote several backends to provide some visual representation of the running app:

While Sketches used the IDE editing surface and a custom renderer view for results, with the Inspector we took a different route. Our interactive surface was an HTML canvas, and our results are rendered using HTML. This allowed us to do some pretty visualizations for results.

We have only started to explore what is possible in this space, and our last release included various data renderers. In particular, we added support for pretty printing collections and a handful of native Android and iOS results.

Up until now, we had been powered by Mono's C# compiler and while it has served us well for many years, it pales in comparison with the services that we could get out of Microsoft's Roslyn. Our code completion and error reporting were limited and the model did not translate too well to F#.

We recently switched the inspector to use Roslyn:

With this release, we ended up with an Inspector that can now be used either to debug/analyze a running app (very much like a web inspector), or one that can be used to experiment with APIs in the same spirit as other shells.

Continuous

In the meantime, Frank Krueger took the iOS support that we introduced for the compiler as a service, and wrote Continuous, a plug-in for Xamarin Studio and Visual Studio that allowed developers to live-code. That is, instead of using this as a separate tool, you can modify your classes and methods live and have your application update as you change the code:

Frank also added support for evaluating values immediately, and showing some values in comments, similar in spirit to his Calca app for iOS:

The Glorious Future

But now that we have a powerful HTML rendering engine to display our results and we upgraded our compiler engine, we are ready to take our next steps.

One step will be to add more visualizers and rendering capabilties to our results in our Inspector.

The second step is to upgrade Sketches based on this work. We will be changing the Sketches UI to be closer to IPython, that is, the ability of creating workbooks that contain both rich HTML text along with live code.

To give you a taste of what is coming up on our next release, check out this screenshot:

Developers will still have a few options of richly interacting with C# and F#:

- With our inspector experiment with APIs like they do with many other interactive shells, and to poke and modify running apps on a wide spectrum of environments.

- With Frank Krueger's Continuous engine to see your changes live for your C# code.

- With our revamped Sketches/workbook approach to use it for creating training, educational materials.

Posted on 17 Feb 2016

Shared Projects or PCL?

My colleague Jason Smith has shared his views on what developers should use when trying to share code between projects. Should you go with a Shared Project or a Portable Class Library (PCL) in the world of Xamarin.Forms?

He hastily concludes that you should go with PCLs (pronounced Pickles).

For me, the PCL is just too cumbersome for most uses. It is like using a canon to kill a fly. It imposes too many limitations (limited API surface), forces you to jump through hoops to achieve some very basic tasks.

PCLs when paired with Nugets are unmatched. Frameworks and library authors should continue to deliver these, because they have a low adoption barrier and in general bring smiles and delight to their users.

But for application developers, I stand firmly on the opposite side of Jason.

I am a fan of simplicity. The simpler the technology, the easier it is for you to change things. And when you are building mobile applications chances are, you will want to make sweeping changes, make changes continously and these are just not compatible with the higher bar required by PCLs.

Jason does not like #if statements on his shared code. But this is not the norm, it is an exception. Not only it is an exception, but careful use of partial classes in C# make this a non issue.

Plugging a platform specific feature does not to use an #if block, all you have to do is isolate the functioanlity into a single method, and have each platform that consumes the code implement that one method. This elegant idea is the same elegant idea that makes the Linux kernel source code such a pleasure to use - specific features are plugged, not #ifdefed.

If you are an application developer, go with Shared Projects for your shared code. And now that we support this for F#, there is no reason to not adopt them.

Posted on 22 Jan 2016

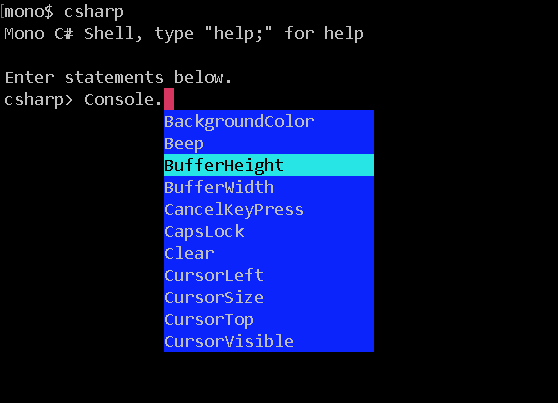

getline.cs update: Partying like it is 1992

Back in 2008, I wrote about getline.cs, a single-file command line editor for shell application. It included Emacs key bindings, history, customizable completion and incremental search. It is equivalent to GNU's readline library, except it is implemented in a single C# file.

I recently updated getline.cs to add a popup-based

completion and C# heuristics for when to automatically trigger

code completion. This is what it looks like when using in

Mono's

C# REPL in the command line:

Posted on 14 Jan 2016

Mono's Cooperative Mode for SGen GC

Mono's master tree now contains support for a new mode of operation for our garbage collector, we call this the cooperative mode. This is in contrast with the default mode of operation, the preemptive mode.

This mode is currently enabled by setting the MONO_ENABLE_COOP environment variable.

We implemented this new mode of operation to make it simpler to debug our GC, to have access to more data on the runtime during GC times and also to support certain platforms that do not provide the APIs that our preemptive system needed.

Behind Preemptive Mode

When we started building Mono back in 2001, we wanted to get something up and running very quickly. The idea was to have enough of a system running on Linux that we could have a fully self-hosting C# environment in a short period of time, and we managed to do this within eight months.

We were very lucky when it came to garbage collection that the fabulous Boehm GC existed. We were able to quickly add garbage collection to Mono, without having to think much about the problem.

Boehm is fabulous because it does not really require the cooperation of the runtime to work. It is a garbage collector that was originally designed to add garbage collection capabilities to programs written in C or C++. It performs garbage collection without much developer intervention. And it achieves this for existing code: multi-threaded, assembly-loving, low-level code.

Boehm GC is a thing of beauty.

Boehm achieves its magic by pulling some very sophisticated low-level tricks. For example, when it needs to perform a garbage collection it relies on various operating system facilities to stop all running threads, examine the stacks for all these threads to gather roots from the stack, perform the actual GC job then resume the operation of the program.

While Boehm is fantastic, in Mono, we had needs that would be better served with a custom garbage collector. One that was generational and reduced collection times. One fit more closely with .NET. It was then that we built the current GC for Mono: SGen.

SGen has grown by leaps and bounds and has been key in supporting many advanced scenarios on Android and iOS as well as being a higher performance and lower latency GC for Mono.

When we implemented SGen, we had to make some substantial changes to Mono's code generator. This was the first time that Mono's code generator had to coordinate with the GC.

SGen kept a key feature of Boehm: most running code was blissfully unaware that it could be stopped and resumed at any point.

This meant that we did not have to do too much work to integrate SGen into Mono [1]. There are two main downsides with this.

The first downside is that we still required the host platform to support some mechanism to stop, resume and inspect threads. This alone is pretty obnoxious and caused much grief to developers porting Mono to strange platforms.

The second downside is that code that runs during the collection is not really allowed to use many of the runtime APIs or primitives, because the collector might be running in parallel to the regular code. You can only use reentrant code.

This is a major handicap for development and debugging of the collector. One that is just too obnoxious to deal with and one that has wasted too much of our time.

Cooperative Mode

In the new cooperative mode, the generated code is instrumented to support voluntarily stopping execution

Conceptually, you can think of the generated code as one that basically checks on every back-branch, or every call site that the collector has requested for the thread to stop.

The supporting Mono runtime has been instrumented as well to deal with this scenario. This means that every API that is implemented in the C runtime has been audited to determine whether it can run in a finite amount of time, or if it is a blocking operation and adjusted to participate accordingly.

For methods that run in a finite amount of time, we just wait for them to return back to managed code, where we will stop.

For methods that might potentially block, we need to add some annotations that inform our GC that it is safe to assume that the thread is not running any mutating code. Consider the internal call that implements the CreateDirectory method. It now has been decorated with MONO_PREPARE_BLOCKING and MONO_FINISH_BLOCKING to delimit blocking code.

This means that threads do not stop right away as they used to, but they stop soon enough. And it turns out that soon enough is good enough.

This has a number of benefits. First, it allows us to support platforms that do not have enough system primitives to stop, resume and examine arbitrary threads. Those include things like the Windows Store, WatchOS and various gaming consoles.

But selfishly, the most important thing for us is that we will be able to treat the garbage collector code as something that is a first class citizen in the runtime: when the collector works, it will be running in such a state that accessing various runtime structures is fine (or even using any tasty C libraries that we choose to use).

Today

As of today, Mono's Coop engine can either be compiled in by default (by passing --with-cooperative-gc to configure), or by setting the MONO_ENABLE_COOP environment variable to any value.

We have used a precursor of Coop for about 18 months, and now we have a fully productized version of it on Mono master and we are looking for developers to try it out.

We are hoping to enable this by default next year. [1] Astute readers will notice that it still took years of development to make SGen the default collector in Mono.

Posted on 22 Dec 2015

David Brooks, Op-Ed for All Trades, Master of None

I first heard about David Brooks' article criticizing Most Likely to Succeed from a Mom at school that told me it was a rebuttal to the movie, and I should check it out.

I nodded, but did not really expect the article to change my mind.

David Brooks is an all-terrain commentator which dispenses platitudes and opinions on a wide range of topics, usually with little depth or understanding. In my book, anyone that supported and amplified the very fishy evidence for going to war with Iraq has to go an extra mile to prove their worth - and he was specially gross when it came to it.

Considering that the best part about David Brook's writing is that they often prompt beautiful take downs from Matt Taibbi and that his columns have given rise to a cottage industry of bloggers that routinely point out just how wrong he is, my expectations were low.

Anyways, I did read the article.

While the tone of the article is a general disagreement with novel approaches to education, his prescription is bland and generic: you need some basic facts before you can build upon those facts and by doing this, you will become a wise person.

The question of course is just how many facts? Because it is one thing to know basic facts about our world like the fact that there are countries, and another one to memorize every date and place of a historic event.

But you won't find an answer to that on Brooks piece. If there is a case to be made to continue our traditional education and continue relying on tests to raise great kids, you will not find it here.

The only thing that transpires from the article is that he has not researched the subject - he is shooting from the hip. An action necessitated by the need to fill eight hundred words a short hour before lunch.

His contribution to the future of education brings as much intellectual curiosity as washing the dishes.

I rather not shove useless information into our kids. Instead we should fill their most previous years with joy and passion, and give them the tools to plot their own destinies. Raise curious, critical and confident kids.

Ones that when faced with a new problem opt for the more rewarding in-depth problem solving, one that will have them research, reach out to primary sources, and help us invent the future.

Hopefully we can change education and raise a happier, kinder and better generation of humans. The road to get there will be hard, and we need to empower the teachers and schools that want to bring this change.

"Most Likely to Succeed" represends Forward Motion, and helps us start this discussion, and David's opinions should be dismissed for what they are: a case of sloppy stop energy.

Do not miss Ted Dintersmith's response to the article, my favorite part:

I agree with Brooks that some, perhaps even many, gain knowledge and wisdom over time. We just don’t gain it in school. It comes when we’re fully immersed in our careers, when we do things, face setbacks, apply our learning, and evolve and progress. But that almost always comes after our formal education is over. I interview a LOT of recent college graduates and I’m not finding lots of knowledge and wisdom. Instead, I find lots of student debt, fear of failure, and formulaic thinking. And what do I rarely see? Passion, purpose, creativity, and audacity.

So, game on, David Brooks and others defending the 19th Century model of education.

Posted on 19 Oct 2015

Roslyn in MonoDevelop/XamarinStudio

As promised, we now have a version of our IDE powered by Roslyn, Microsoft's open sourced C# compiler as a service

When we did the port we found various leaks in the IDE that were made worse by Roslyn, so we decided to take the time and fix those leaks, and optimize our use of Roslyn.

Next Steps

We want to get your feedback on how well it works and to let us know what problems you are running into. Once we feel that there are no regressions, we will make this part of the default IDE.

While Roslyn is very powerful, this power comes with a memory consumption price tag. The Roslyn edition of Xamarin Studio will use more memory.

We are working to reduce Roslyn's and Xamarin Studio memory usage in future versions.

Posted on 21 Sep 2015

Mono and LLVM's BitCode

This past June, Apple announced that WatchOS 2 applications would have to be submitted using LLVM BitCode. The idea being that Apple could optimize your code as new optimizations are developed or new CPU features are introduced, and users would reap the benefits without requiring the developer to resubmit their applications.

BitCode is a serialized version of the low-level intermediate representation used by LLVM.

WatchOS 2 requires pure BitCode to be submitted. That is, BitCode that does not contain any machine code blobs. iOS supports mixed mode BitCode, that is, BitCode that contains both the LLVM intermediate representation code, and blobs of machine code.

While Mono has had an LLVM backend for a long time, generating pure BitCode posed a couple of challenges for us.

First, Mono's LLVM backend does not cover all the generated code. There were some corner cases that we handled with Mono's old code generator. Also, Mono uses hand-written assembly language code in various places (lots of small optimizations involving generics code sharing, method dispatch and other things like that). This poses a problem for WatchOS.

Secondly, Mono uses a modified version of LLVM that adds support for many .NET idioms. In particular, our changes to LLVM produce the necessary information to support .NET-style exception handling [1].

We spent the summer adapting Mono to produce Vanilla LLVM bitcode support. This includes the removal of our hand-tuned machine code, as well as devising a new system for exception handling that works in this context. Sadly, the exception handling is not as efficient as the one that we got with our modified LLVM.

Hopefully, we will be able to upstream our changes for better exception handling for .NET-like languages to LLVM in the future and get some of the performance back.

Notes

[1] Vanilla LLVM exception support requires exceptions to be explicit. In .NET some exceptions happen implicitly, for example, when dereferencing a null pointer, or dividing by zero.

Posted on 02 Sep 2015

Xamarin Release Cycles

There are four major components of Xamarin's platform product: the Android SDK, the iOS SDK, our Xamarin Studio IDE and our Visual Studio extension.

In the past, we used to release each component independently, but last year we realized that developing and testing each component against the other ones was getting too expensive, too slow and introduced gratuitous errors.

So we switched to a new style of releases where all the components ship together at the same time. We call these cycles.

We have been tuning the cycle releases. We started with time-based releases on a monthly basis, with the idea that any part of the platform that wanted to be released could catch one of these cycles, or wait for the next cycle if they did not have anything ready.

While the theory was great, the internal dependencies of these components was difficult to break, so our cycles started taking longer and longer.

On top of the cycles, we would always prepare builds for new versions of Android and iOS, so we could do same-day releases of the stacks. These are developed against our current stable cycle release, and shipped when we need to.

We are now switching to feature-based releases. This means that we are now waiting for features to be stable, with long preview periods to ensure that no regressions are introduced.

Because feature based releases can take as long as it is needed to ship a feature, we have introduced Service Releases on top of our cycles.

Our Current Releases

To illustrate this scenario, let me show what our current platform looks like.

We released our Cycle 5 to coincide with the Build conference, back in April 29th. This was our last timed release (we call this C5).

Since then we have shipped three service releases which contain important bug fixes and minor features (C5-SR1, SR2 and SR3), with a fourth being cooked in the oven right now (C5-SR4)

During this time, we have issued parallel previews of Android M and iOS 9 support, those are always built on top of the latest stable cycle. Our next iOS 9 preview for example, will be based on the C5-SR4.

We just branched all of our products for the next upgrade to the platform, Cycle 6.

This is the cycle that is based on Mono 4.2.0 and which contains a major upgrade to our Visual Studio support for iOS and plenty of improvements to Xamarin Studio. I will cover some of my favorite features in Cycle 6 in future posts.

Posted on 01 Sep 2015

« Newer entries | Older entries »

Blog Search

Archive

- 2024

Apr Jun - 2020

Mar Aug Sep - 2018

Jan Feb Apr May Dec - 2016

Jan Feb Jul Sep - 2014

Jan Apr May Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2012

Feb Mar Apr Aug Sep Oct Nov - 2010

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2008

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2006

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2004

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2002

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Dec

- 2022

Apr - 2019

Mar Apr - 2017

Jan Nov Dec - 2015

Jan Jul Aug Sep Oct Dec - 2013

Feb Mar Apr Jun Aug Oct - 2011

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2009

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2007

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2005

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2003

Jan Feb Mar Apr Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2001

Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec