SwiftNavigation

To celebrate that RealityKit's is coming to MacOS, iOS and iPadOS and is no longer limited to VisionOS, I am releasing SwiftNavigation for RealityKit.

Last year, as I was building a game for VisionPro, I wanted the 3D characters I placed in the world to navigate the world, go from one point to another, avoid obstacles and have those 3D characters avoid each other.

Almost every game engine in the world uses the C++ library RecastNavigation library to do this - Unity, Unreal and Godot all use it.

SwiftNavigation was born: Both a Swift wrapper to the underlying C++ library which leverages extensively Swift's C++ interoperability capabilities and it directly integrates into the RealityKit entity system.

This library is magical, you create a navigation mesh from the world that you capture and then you can query it for paths to navigate from one point to another or you can create a crowd controller that will automatically move your objects.

Until I have the time to write full tutorials, your best bet is to look at the example project that uses it.

Posted on 11 Jun 2024

Embeddable Game Engine

Many years ago, when working at Xamarin, where we were building cross-platform

libraries for mobile developers, we wanted to offer both 2D and 3D gaming

capabilities for our users in the form of adding 2D or 3D content to their

mobile applications.

Many years ago, when working at Xamarin, where we were building cross-platform

libraries for mobile developers, we wanted to offer both 2D and 3D gaming

capabilities for our users in the form of adding 2D or 3D content to their

mobile applications.

For 2D, we contributed and developed assorted Cocos2D-inspired libraries.

For 3D, the situation was more complex. We funded a few over the years, and we contributed to others over the years, but nothing panned out (the history of this is worth a dedicated post).

Around 2013, we looked around, and there were two contenders at the time, one was an embeddable engine with many cute features but not great UI support called Urho, and the other one was a Godot, which had a great IDE, but did not support being embedded.

I reached out to Juan at the time to discuss whether Godot could be turned into such engine. While I tend to take copious notes of all my meetings, those notes sadly were gone as part of the Microsoft acquisition, but from what I can remember Juan told me, "Godot is not what you are looking for" in two dimensions, there were no immediate plans to turn it into an embeddable library, and it was not as advanced as Urho, so he recommended that I go with Urho.

We invested heavily in binding Urho and created UrhoSharp that would go into becoming a great 3D library for our C# users and worked not only on every desktop and mobile platform, but we did a ton of work to make it great for AR and VR headsets. Sadly, Microsoft's management left UrhoSharp to die.

Then, the maintainer of Urho stepped down, and Godot became one of the most popular open-source projects in the world.

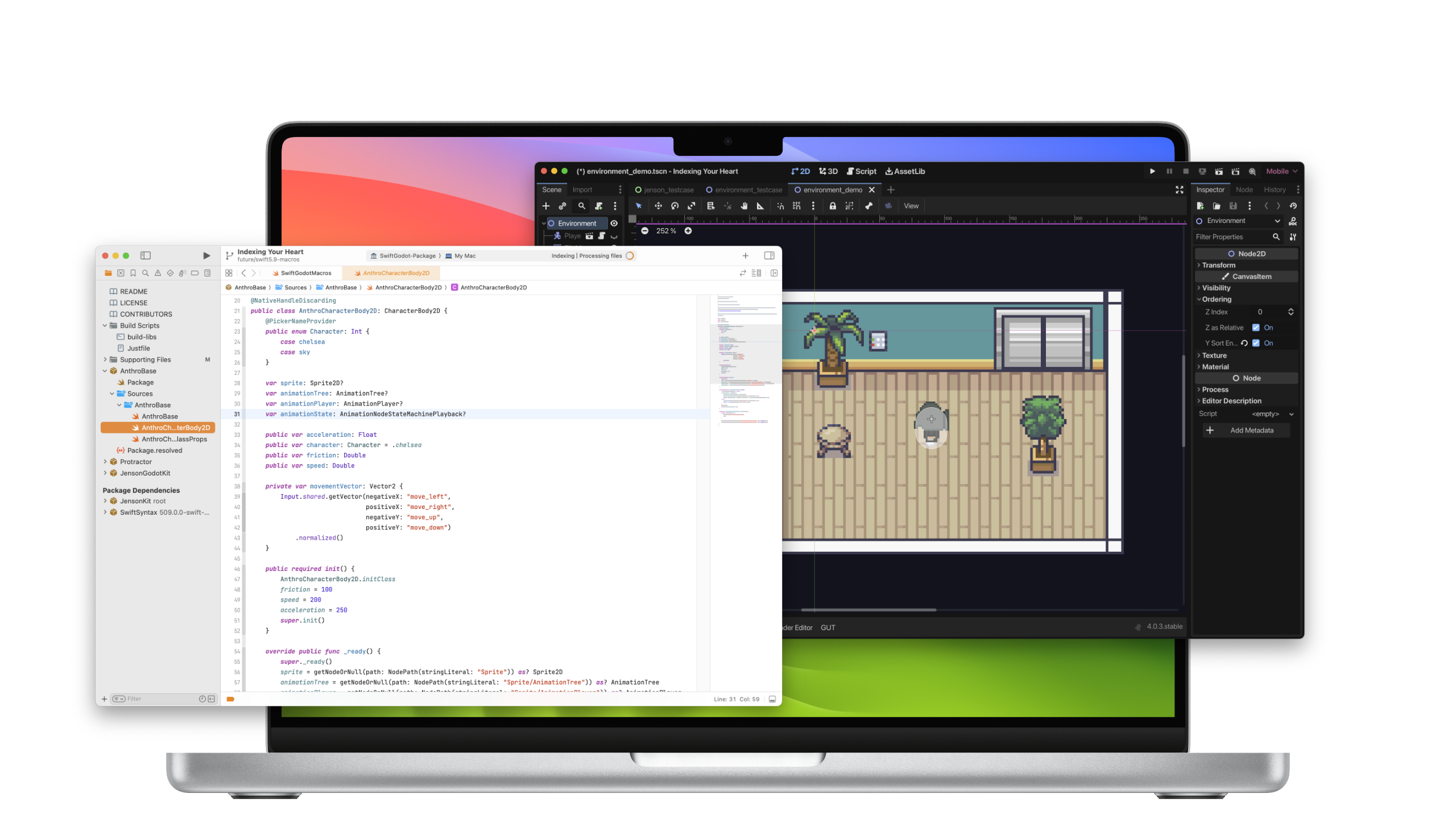

Last year, @Faolan-Rad contributed a patch to Godot to turn it into a library that could be embedded into applications. I used this library to build SwiftGodotKit and have been very happy with it ever since - allowing people to embed Godot content into their application.

However, the patch had severe limitations; it could only ever run one Godot game as an embedded system and could not do much more. The folks at Smirk Software wanted to take this further. They wanted to host independent Godot scenes in their app and have more control over those so they could sprinkle Godot content at their heart's content on their mobile app (demo)

They funded some initial work to do this and hired Gergely Kis's company to do this work.

Gergely demoed this work at GodotCon last year. I came back very excited from GodotCon and I decided to turn my prototype Godot on iPad into a complete product.

One of the features that I needed was the ability to embed chunks of Godot in discrete components in my iPad UI, so we worked with Gergely to productize and polish this patch for general consumption.

Now, there is a complete patch under review to allow people to embed arbitrary

Godot scenes into their apps. For SwiftUI users, this means that you can embed a Godot scene into a View and display and control it at will.

Hopefully, the team will accept this change into Godot, and once this is done, I will update SwiftGodotKit to get these new capabilities to Swift users (bindings for other platforms and languages are left as an exercise to the reader).

It only took a decade after talking to Juan, but I am back firmly in Godot land.

Posted on 23 Apr 2024

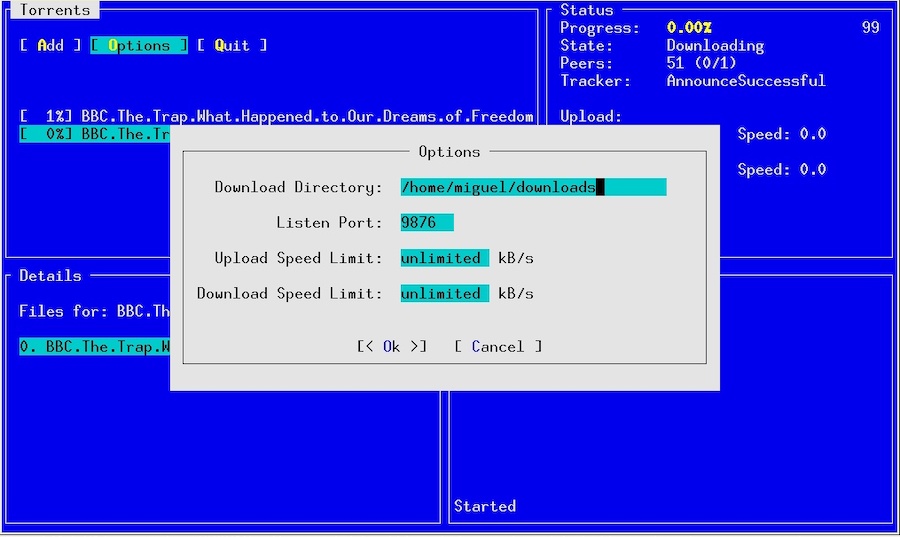

SwiftTermApp: SSH Client for iOS

For the past couple of years, programming in Swift has been a guilty pleasure of mine - I would sneak out after getting the kids to sleep to try out the latest innovations in iOS, such as SwiftUI and RealityKit. I have decided to ship a complete app based on this work, and I put together an SSH client for iOS and iPadOS using my terminal emulator, which I call “SwiftTermApp.”

What it lacks in terms of an original name, it makes up for by having solid fundamentals in place: a comprehensive terminal emulator with all the features you expect from a modern terminal emulator, good support for international input and output, tasteful use of libssh2, keyboard accessories for your Unix needs, storing your secrets in the iOS keychain, extensive compatibility tests, an embrace of the latest and greatest iOS APIs I could find, and is fuzzed and profiled routinely to ensure a solid foundation.

While I am generally pleased with the application for personal use, my goal is to make this app generally valuable to users that routinely use SSH to connect to remote hosts - and nothing brings more clarity to a product than a user’s feedback.

I would love for you to try this app and help me identify opportunities and additional features for it. These are some potential improvements to the app, and I could use your help prioritizing them:

- iOS Capabilities:

- App capabilities:

- Terminal Emulation:

- Experience improvements:

To reduce my development time and maximize my joy, I built this app with SwiftUI and the latest features from Swift and iOS, so it won't work on older versions of iOS. In particular, I am pretty happy with what Swift async enabled me to do, which I hope to blog about soon.

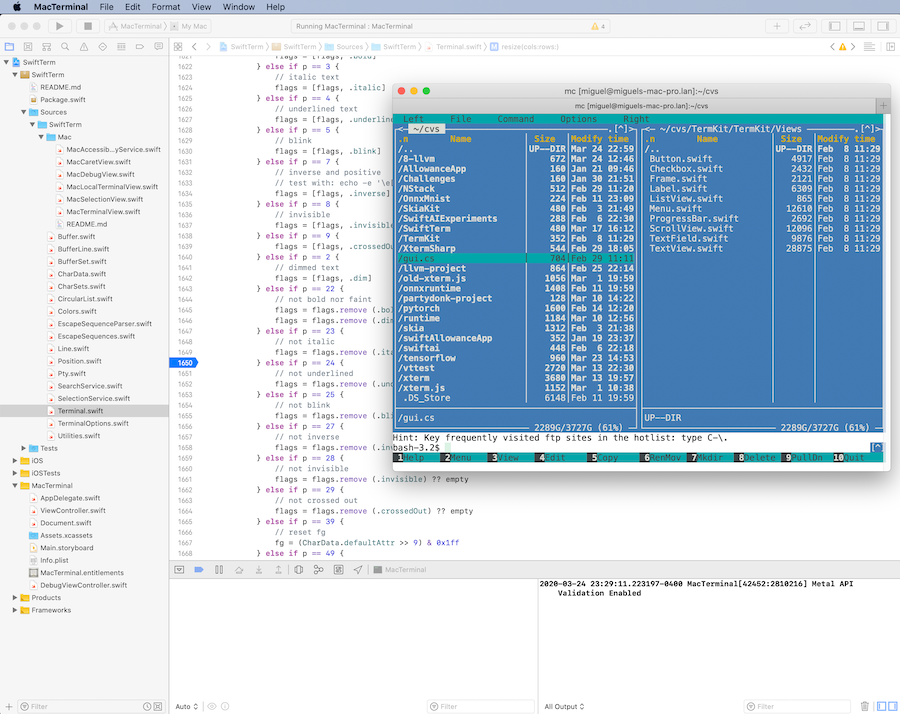

SwiftTermApp is part of a collection of open-source code built around the Unix command line that I have been authoring on and off for the past 15 years. First in C#, now also in Swift. If you are interested in some of the other libraries, check out my UI toolkits for console applications (gui.cs for C#, and TermKit for Swift) and my xterm/vt100 emulator libraries (XtermSharp for C# and SwiftTerm for Swift). I previously wrote about how they came to be.

Update: Join the discussion

For later:

For a few months during the development of the SwiftTerm library, I worked to ensure great compatibility with other terminal emulators using the esctest and vttest. I put my MacPro to good use during the evenings to run the Swift fuzzer and tracked down countless bugs and denial of service errors, used Instruments religiously to improve the performance of the terminal emulator and ensured a good test suite to prevent regressions.

Original intro: For the past few years, I have been hacking on assorted terminal tools in both C# and Swift, including a couple of UI toolkits for console applications (gui.cs for C#, and TermKit for Swift) and xterm/vt100 emulators (XtermSharp for C# and SwiftTerm for Swift). I previously wrote about how they came to be.

Posted on 06 Apr 2022

AppStore Reviews Should be Stricter

Since the AppStore launched, developers have complained about the review process as too strict. Applications are mostly rejected either for not meeting requirements, not having enough functionality or circumventing Apple’s business model.

Yet, the AppStore reviews are too lax and they should be much stricter.

Let me explain why I think so, what I believe some new rules need to be, and how the AppStore can be improved.

Prioritizing the Needs of the Many

Apple states that they have 28 million registered developers, but I believe that only a fraction of those are actively developing applications on a daily basis. That number is closer to 5 million developers.

I understand deeply why developers are frustrated with the AppStore review process - I have suffered my fair share of AppStore rejections: both by missing simple issues and by trying to push the limits of what was allowed. I founded Xamarin, a company that built tools for mobile developers, and had a chance to become intimately familiar with the rejections that our own customers got.

Yet, there are 1.5 billion active Apple devices, devices that people trust to be keep their data secure and private. The overriding concern should be the 1.5 billion active users, and not the 0.33% (or 1.86% if you are feeling generous).

People have deposited their trust on Apple and Google to keep their devices safe. I wrote about this previously. While it is an industry sport to make fun of Google, I respect the work that Google puts on securing and managing my data - so much that I have trusted them with my email, photographs and documents for more than 15 years.

I trust both companies both because of their public track record, and because of conversations that I have had with friends working at both companies about their processes, their practices and the principles that they care about (Keeping up with Information Security is a part-time hobby of minex).

Today’s AppStore Policies are Insufficient

AppStore policies, and their automated and human reviews have helped nurture and curate the applications that are available. But with a target market as large and rich as iOS and Android these ecosystems have become a juicy target for scammers, swindlers, gangsters, nation states and hackers.

While some developers are upset with the Apple Store rejections, profiteers have figured out that they can make a fortune while abiding by the existing rules. These rules allow behaviors that are in either poor taste, or explicitly manipulating the psyche of the user.

First, let me share my perspective as a parent, and

I have kids aged 10, 7 and 4, and my eldest had access to an iPad since she was a year old, and I have experienced first hand how angering some applications on the AppStore can be to a small human.

It breaks my heart every time they burst out crying because something in these virtual worlds was designed to nag them, is frustrating or incomprehensible to them. We sometimes teach them how to deal with those problems, but this is not always possible. Try explaining to a 3 year old why they have to watch a 30 seconds ad in the middle of a dinosaur game to continue playing, or teach them that at arbitrary points during the game tapping on the screen will not dismiss an ad, but will instead take them to download another app, or direct them another web site.

This is infuriating.

Another problem happens when they play games defective by design. By this I mean that these games have had functionality or capabilities removed that can be solved by purchasing virtual items (coins, bucks, costumes, pets and so on).

I get to watch my kids display a full spectrum of negative experiences when they deal with these games.

We now have a rule at home “No free games or games with In-App Purchases”. While this works for “Can I get a new game?”, it does not work for the existing games that they play, and those that they play with their friends.

Like any good rule, there are exceptions, and I have allowed the kids to buy a handful of games with in-app purchases from reputable sources. They have to pay for those from their allowance.

These dark patterns are not limited applications for kids, read the end of this post for a list of negative scenarios that my followers encountered that will ring familiar.

Closing the AppStore Loopholes

Applications using these practices should be banned:

Those that use Dark Patterns to get users to purchase applications or subscriptions: These are things like “Free one week trial”, and then they start charging a high fee per week. Even if this activity is forbidden, some apps that do this get published.

Defective-by-design: there are too many games out there that can not be enjoyed unless you spend money in their applications. They get the kids hooked up, and then I have to deal with whiney 4 year olds, 7 year olds and 10 year old to spend their money on virtual currencies to level up.

Apps loaded with ads: I understand that using ads to monetize your application is one way of supporting the development, but there needs to be a threshold on how many ads are on the screen, and shown by time, as these apps can be incredibly frustrating to use. And not all apps offer a “Pay to remove the ad”, I suspect because the pay-to-remove is not as profitable as showing ads non-stop.

Watch an ad to continue: another nasty problem are defective-by-design games and application that rather than requesting money directly, steer kids towards watching ads (sometimes “watch an ad for 30 seconds”) to get something or achieve something. They are driving ad revenue by forcing kids to watch garbage.

Install chains: there are networks of ill-behaved applications that trick kids into installing applications that are part of their network of applications. It starts with an innocent looking app, and before the day is over, you are have 30 new scammy apps installed on your machine.

Notification Abuse: these are applications that send advertisements or promotional offers to your device. From discount offers, timed offers and product offerings. It used to be that Apple banned these practices on their AppReview guidelines, but I never saw those enforced and resorted to turning off notifications. These days these promotions are allowed. I would like them to be banned, have the ability to report them as spam, and infringers to have their notification rights suspended.

) Ban on Selling your Data to Third Parties: ban applications that sell your data to third parties. Sometimes the data collection is explicit (for example using the Facebook app), but sometimes unknowingly, an application uses a third party SDK that does its dirty work behind the scenes. Third party SDKs should be registered with Apple, and applications should disclose which third party SDKs are in use. If one of those 3rd party SDKs is found to abuse the rules or is stealing data, all applications that rely on the SDK can be remotely deactivated. While this was recently in the news this is by no means a new practice, this has been happening for years.

) Ban on Selling your Data to Third Parties: ban applications that sell your data to third parties. Sometimes the data collection is explicit (for example using the Facebook app), but sometimes unknowingly, an application uses a third party SDK that does its dirty work behind the scenes. Third party SDKs should be registered with Apple, and applications should disclose which third party SDKs are in use. If one of those 3rd party SDKs is found to abuse the rules or is stealing data, all applications that rely on the SDK can be remotely deactivated. While this was recently in the news this is by no means a new practice, this has been happening for years.

One area that is grayer are Applications that are designed to be addictive to increase engagement (some games, Facebook and Twitter) as they are a major problem for our psyches and for our society. Sadly, it is likely beyond the scope of what the AppStore Review team can do. One option is to pass legislation that would cover this (Shutdown Laws are one example).

Changes in the AppStore UI

It is not apps for children that have this problem. I find myself thinking twice before downloading applications with "In App Purchases". That label has become a red flag: one that sends the message "scammy behavior ahead"

I would rather pay for an app than a free app with In-App Purchases. This is unfair to many creators that can only monetize their work via an In-App Purchases.

This could be addressed either by offering a free trial period for the app (managed by the AppStore), or by listing explicitly that there is an “Unlock by paying” option to distinguish these from “Offers In-App Purchases” which is a catch-all expression for both legitimate, scammy or nasty sales.

My list of wishes:

Offer Trial Periods for applications: this would send a clear message that this is a paid application, but you can try to use it. And by offering this directly by the AppStore, developers would not have to deal with the In-App purchase workflow, bringing joy to developers and users alike.

Explicit Labels: Rather than using the catch-all “Offers In-App Purchases”, show the nature of the purchase: “Unlock Features by Paying”, “Offers Subscriptions”, “Buy virtual services” and “Sells virtual coins/items”

Better Filtering: Today, it is not possible to filter searches to those that are paid apps (which tend to be less slimy than those with In-App Purchases)

Disclose the class of In-App Purchases available on each app that offers it up-front: I should not have to scroll and hunt for the information and mentally attempt to understand what the item description is to make a purchase

Report Abuse: Human reviewers and automated reviews are not able to spot every violation of the existing rules or my proposed additional rules. Users should be able to report applications that break the rules and developers should be aware that their application can be removed from circulation for breaking the rules or scammy behavior.

Some Bad Practices

Check some of the bad practices in this compilation

Posted on 24 Sep 2020

Some Bad App Practices

Some bad app patterns as some followers described them

Graphics is a big part of it. It also tries to make you purchase random things that have nothing to do with answering trivia questions. pic.twitter.com/hLDhd2QIbG

— Meher Kasam (@MeherKasam) August 28, 2020

"PicJointer Photo Collage Maker", a low end app which just makes one jpeg from several jpegs, is "free"

— Jo Shields (@directhex) August 27, 2020

with a 1 week trial

then costs more than a Netflix sub

So many dark patterns in games. I remember downloading Tiny Tower back in the day and being blown away that you would be told to stop playing and come back in an hour to play more. We made a house rule that we don't play games with gems, they're all optimized for addiction/profit

— Tom Finnigan (@tomfinnigan) August 27, 2020

YouTube's _agressive_ prompts to pay instead of ads led me to delete it. Despise it.

— Kevin Jones 🏳️🌈 (@vcsjones) August 27, 2020

I generally avoid games that are not on Apple Arcade. Every game I've downloaded desperately pushes micro transactions to make progress after a few hours of investment.

My daughter downloaded a free quiz game, that started charging a subscription of $60 per WEEK.

— Cam Foale (@kibibu) August 28, 2020

Legit apps do some shit stuff. Grab (car hire) recently threw up a screen as I was booking a car and I thought I was dismissing it, but what I was doing was enrolling in an insurance scheme for an extra $.30 per ride going forward and no idea how to turn it off.

— Alan Graham: he’s just this guy, you know? (@agraham999) August 27, 2020

Top-rated Sudoku app on the App Store had you accept a privacy policy which contained language that they tracked your location while playing. Sudoku!

— Mihai Chereji (@croncobaurul) August 28, 2020

You can read more in the replies to my request a few weeks ago:

Have you downloaded an app and had an unsavory experience? Scammy, swindley, dark patterny? Share with me your bad experiences.

— Miguel de Icaza (@migueldeicaza) August 27, 2020

Posted on 23 Sep 2020

Apple versus Epic Games: Why I’m Willing to Pay a Premium for Security, Privacy, and Peace of Mind

In the legal battle over the App Store’s policies, fees, and review processes, Epic Games wants to see a return to the good old days – where software developers retained full control over their systems and were only limited by their imaginations. Yet those days are long gone.

Granted, in the early 90s, I hailed the Internet as humanity’s purest innovation. After all, it had enabled a group of global developers to collaboratively build the Linux operating system from the ground up. In my X years of experience as a developer, nothing has come close to the good will, success, and optimistic mood of those days.

Upon reflection, everything started to change the day I received my first spam message. It stood out not only because it was the first piece of unsolicited email I received, but also because it was a particularly nasty piece of spam. The advertiser was selling thousands of email addresses for the purposes of marketing and sales. Without question, I knew that someone would buy that list, and that I would soon be on the receiving end of thousands of unwanted pieces of mail. Just a few months later, my inbox was filled with garbage. Since then, the Internet has become increasingly hostile – from firewalls, proxies, and sandboxes to high-profile exploits and attacks.

Hardly a new phenomenon, before the Internet, the disk operating system (DOS) platform was an open system where everyone was free to build and innovate. But soon folks with bad intentions destroyed what was a beautiful world of creation and problem solving, and turned it into a place riddled with viruses, trojans, and spyware.

Like most of you alive at the time, I found myself using anti-virus software. In fact, I even wrote a commercial product in Mexico that performed the dual task of scanning viruses and providing a Unix-like permission system for DOS (probably around 1990). Of course, it was possible to circumvent these systems, considering DOS code had full access to the system.

In 1993, Microsoft introduced a family of operating systems that came to be known as Windows NT. Though it was supposed to be secure from the ground up, they decided to leave a few things open due to compatibility concerns with the old world of Windows 95 and DOS. Not only were there bad faith actors in the space, developers had made significant mistakes. Perhaps not surprisingly, users began to routinely reinstall their operating systems following the gradual decays that arose from improper changes to their operating systems.

Fast-forward to 2006 when Windows Vista entered the scene – attempting to resolve a class of attacks and flaws. The solution took many users by surprise. It’s more apt to say that it was heavily criticized and regarded as a joke in some circles. For many, the old way of doing things had been working just fine and all the additional security got in the way. While users hated the fact that software no longer worked out of the box, it was an important step towards securing systems.

With the benefit of hindsight, I look back at the early days of DOS and the Internet as a utopia, where good intentions, innovation, and progress were the norm. Now swindlers, scammers, hackers, gangsters, and state actors routinely abuse open systems to the point that they have become a liability for every user.

In response, Apple introduced iOS – an operating system that was purpose-build to be secure. This avoided backwards compatibility problems and having to deal with users who saw unwanted changes to their environment. In a word, Apple managed to avoid the criticism and pushback that had derailed Windows Vista.

It’s worth pointing out that Apple wasn’t the first to introduce a locked-down system that didn’t degrade. Nintendo, Sony, and Microsoft consoles restricted the software that could be modified on their host operating systems and ran with limited capabilities. This resulted in fewer support calls, reduced frustration, and limited piracy.

One of Apple’s most touted virtues is that the company creates secure devices that respect user’s privacy. In fact, they have even gone to court against the US government over security. Yet iOS remains the most secure consumer operating system. This has been made possible through multiple layers of security that address different threats. (By referring to Apple’s detailed platform security, you can get a clear sense of just how comprehensive it is.)

Offering a window into the development process, security experts need to evaluate systems from end-to-end and explore how the system can be tampered with, attacked, or hacked, and then devise both defense mechanisms and plans for when things will inevitably go wrong.

Consider the iPhone. The hardware, operating system, and applications were designed with everything a security professional loves in mind. Even so, modern systems are too large and too complex to be bullet-proof. Researchers, practitioners, hobbyists, and businesses all look for security holes in these systems – some with the goal of further protecting the system, others for educational purposes, and still others for profit or to achieve nefarious goals.

Whereas hobbyists leverage these flaws to unlock their devices and get full control over their systems, dictatorships purchase exploits in the black market to use against their enemies and gain access to compromising data, or to track the whereabouts of their targets.

This is where the next layer of security comes in. When a flaw is identified – whether by researchers, automated systems, telemetry, or crashes – software developers design a fix for the problem and roll out the platform update. The benefits of keeping software updated extend beyond a few additional emoji characters; many software updates come with security fixes. Quite simply, updating your phone keeps you more secure. However, it’s worth emphasizing that this only works against known attacks.

The App Store review process helps in some ways; namely, it can:

Force applications to follow a set of guidelines aimed at protecting privacy, the integrity of the system, and meet the bar for unsuspecting users

Reduce applications with minimal functionality – yielding less junk for users to deal with and smaller attack surfaces

Require a baseline of quality, which discourages quick hacks

Prevent applications from using brittle, undocumented, or unsupported capabilities

Still, the App Store review process is not flawless. Some developers have worked around these restrictions by: (1) distributing hidden payloads, (2) temporarily disabling features while their app was being tested on Apple’s campus, (3) using time triggers, or (4) remotely controlling features to evade reviewers.

As a case in point, we need look no further than Epic Games. They deceptively submitted a “hot fix,” which is a practice used to fix a critical problem such as a crash. Under the covers, they added a new purchasing system that could be remotely activated at the time of their choosing. It will come as no surprise that they activated it after they cleared the App Store’s review process.

Unlike a personal computer, the applications you run on your smartphone are isolated from the operating system and even from each other to prevent interference. Since apps run under a “sandbox” that limits what they can do, you do not need to reinstall your iPhone from scratch every few months because things no longer work.

Like the systems we described above, the sandbox is not perfect. In theory, a bad actor could include an exploit for an unknown security hole in their application, slip it past Apple, and then, once it is used in the wild, wake up the dormant code that hijacks your system.

Anticipating this, Apple has an additional technical and legal mitigation system in place. The former allows Apple to remotely disable and deactivate ill-behaved applications, in cases where an active exploit is being used to harm users. The legal mitigation is a contract that is entered into between Apple and the software developer, which can be used to bring bad actors to court.

Securing a device is an ongoing arms race, where defenders and attackers are constantly trying to outdo the other side, and there is no single solution that can solve the problem. The battlegrounds have recently moved and are now being waged at the edges of the App Store’s guidelines.

In the same way that security measures have evolved, we need to tighten the App Store’s guidelines, including the behaviors that are being used for the purposes of monetization and to exploit children. (I plan to cover these issues in-depth in a future post.) For now, let me just say that, as a parent, there are few things that would make me happier than more stringent App Store rules governing what applications can do. In the end, I value my iOS devices because I know that I can trust them with my information because security is paramount to Apple.

Coming full-circle, Epic Games is pushing for the App Store to be a free-for-all environment, reminiscent of DOS. Unlike Apple, Epic does not have an established track record of caring about privacy and security (in fact, their privacy policy explicitly allows them to sell your data for marketing purposes). Not only does the company market its wares to kids, they recently had to backtrack on some of their most questionable scams – i.e., loot boxes – when the European Union regulated them. Ultimately, Epic has a fiduciary responsibility to their investors to grow their revenue, and their growth puts them on a war path with Apple.

In the battle over the security and privacy of my phone, I am happy to pay a premium knowing that my information is safe and sound, and that it is not going to be sold to the highest bidder.

Posted on 28 Aug 2020

Yak Shaving - Swift Edition

At the TensorFlow summit last year, I caught up with Chris Lattner who was at the time working on Swift for TensorFlow - we ended up talking about concurrency and what he had in mind for Swift.

I recognized some of the actor ideas to be similar to those from the Pony language which I had learned about just a year before on a trip to Microsoft Research in the UK. Of course, I pointed out that Pony had some capabilities that languages like C# and Swift lacked and that anyone could just poke at data that did not belong to them without doing too much work and the whole thing would fall apart.

For example, if you build something like this in C#:

class Chart {

float [] points;

public float [] Points { get { return points; } }

}

Then anyone with a reference to Chart can go and poke at the internals of the points array that you have surfaced. For example, this simple Plot implementation accidentally modifies the contents:

void Plot (Chart myChart)

{

// This code accidentally modifies the data in myChart

var p = myChart.points;

for (int i = 0; i < p.Length; i++) {

Plot (0, p [i]++)

}

}

This sort of problem is avoidable, but comes at a considerable development cost. For instance, in .NET you can find plenty of ad-hoc collections and interfaces whose sole purpose is to prevent data tampering/corruption. If those are consistently and properly used, they can prevent the above scenario from happening.

This is where Chris politely pointed out to me that I had not quite understood Swift - in fact, Swift supports a copy-on-write model for its collections out of the box - meaning that the above problem is just not present in Swift as I had wrongly assumed.

It is interesting that I had read the Swift specification some three or four times, and I was collaborating with Steve on our Swift-to-.NET binding tool and yet, I had completely missed the significance of this design decision in Swift.

This subtle design decision was eye opening.

It was then that I decided to gain some real hands-on experience in Swift. And what better way to learn Swift than to start with a small, fun project for a couple of evenings.

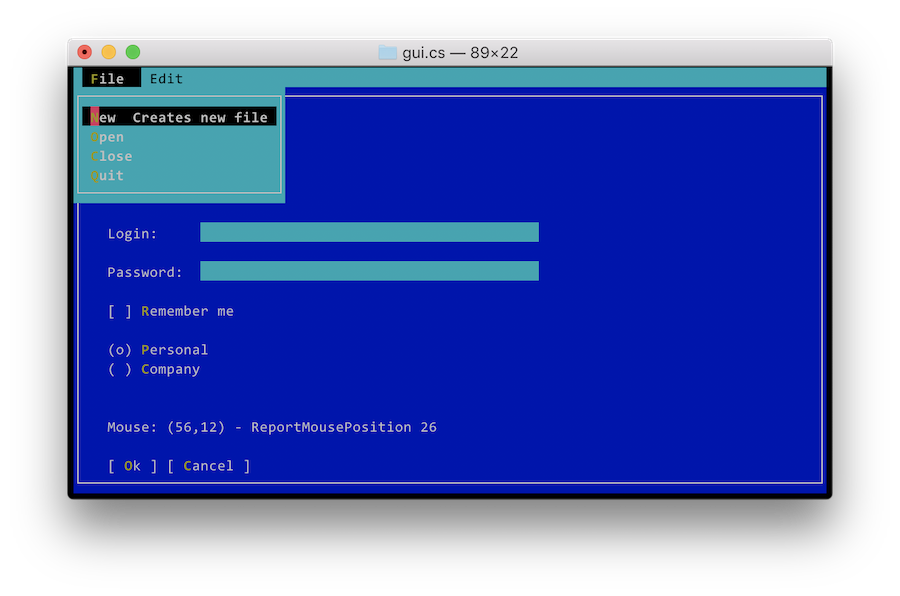

Rather than building a mobile app, which would have been 90% mobile design and user interaction, and little Swift, I decided to port my gui.cs console UI toolkit from C# to Swift and called it TermKit.

Both gui.cs and TermKit borrow extensively from Apple’s UIKit design - it is a design that I have enjoyed. It notably avoids auto layout, and instead uses a simpler layout system that I quite love and had a lot of fun implementing (You can read a description of how to use it in the C# version).

This journey was filled with a number of very pleasant capabilities in Swift that helped me find some long-term bugs in my C# libraries. I remain firmly a fan of compiled languages, and the more checking, the better.

Dear reader, I wish I had kept a log of those but that is now code that I wrote a year ago so I could share all of those with you, but I did not take copious notes. Suffice to say, that I ended up with a warm and cozy feeling - knowing that the compiler was looking out for me.

There is plenty to love about Swift technically, and I will not enumerate all of those features, other people have done that. But I want to point out a few interesting bits that I had missed because I was not a practitioner of the language, and was more of an armchair observer of the language.

The requirement that constructors fully initialize all the fields in a type before calling the base constructor is a requirement that took me a while to digest. My mental model was that calling the superclass to initialize itself should be done before any of my own values are set - this is what C# does. Yet, this prevents a bug where the base constructor can call a virtual method that you override, and might not be ready to handle. So eventually I just learned to embrace and love this capability.

Another thing that I truly enjoyed was the ability of creating a

typealias, which once defined is visible as a new type. A

capability that I have wanted in C# since 2001 and have yet to get.

I have a love/hate relationship with Swift protocols and extensions. I love them because they are incredibly powerful, and I hate them, because it has been so hard to surface those to .NET, but in practice they are a pleasure to use.

What won my heart is just how simple it is to import C code into Swift

- to bring the type definitions from a header file, and call into the C code transparently from Swift. This really is a gift of the gods to humankind.

I truly enjoyed having the Character data type in Swift which

allowed my console UI toolkit to correctly support Unicode on the

console for modern terminals.

Even gui.cs with my port of Go’s Unicode libraries to C# suffers from being limited to Go-style Runes and not having support for emoji (or as the nerd-o-sphere calls it “extended grapheme clusters”).

Beyond the pedestrian controls like buttons, entry lines and checkboxes, there are two useful controls that I wanted to develop. An xterm terminal emulator, and a multi-line text editor.

In the C# version of my console toolkit my multi-line text

editor

was a quick hack. A List<T> holds all the lines in the buffer, and

each line contains the runes to display. Inserting characters is

easy, and inserting lines is easy and you can get this done in a

couple of hours on the evening (which is the sort of time I can devote

to these fun explorations). Of course, the problem is cutting regions

of text across lines, and inserting text that spans multiple lines.

Because what looked like a brilliant coup of simple design, turns out

to be an ugly, repetitive and error-prone code that takes forever to

debug - I did not enjoy writing that code in the end.

For my Swift port, I decided that I needed something better. Of course, in the era of web scale, you gotta have a web scale data structure. I was about to implement a Swift version of the Rope data structure, when someone pointed to me a blog post from the Visual Studio Code team titled “Text Buffer Reimplementation”. I read it avidly, founds their arguments convincing, and in the end, if it is good enough for Visual Studio Code, it should be good enough for the gander.

During my vacation last summer, I decided to port the TypeScript implementation of the Text Buffer to Swift, and named it TextBufferKit. Once again, porting this code from TypeScript to Swift turned out to be a great learning experience for me.

By the time I was done with this and was ready to hook it up to TermKit, I got busy, and also started to learn SwiftUI, and started to doubt whether it made sense to continue work on a UIKit-based model, or if I should restart and do a SwiftUI version. So while I pondered this decision, I did what every other respected yak shaver would do, I proceeded to my xterm terminal emulator work.

Since about 2009 or so, I wanted to have a reusable terminal emulator control for .NET. In particular, I wanted one to embed into MonoDevelop, so a year or two ago, I looked for a terminal emulator that I could port to .NET - I needed something that was licensed under the MIT license, so it could be used in a wide range of situations, and was modern enough. After surveying the space, I found “xterm.js” fit the bill, so I ported it to .NET and modified it to suit my requirements. XtermSharp - a terminal emulator engine that can have multiple UIs and hook up multiple backends.

For Swift, I took the XtermSharp code, and ported it over to Swift, and ended up with SwiftTerm. It is now in quite a decent shape, with only a few bugs left.

I have yet to built a TermKit UI for SwiftTerm, but in my quest for the perfect shaved yak, now I need to figure out if I should implement SwiftUI on top of TermKit, or if I should repurpose TermKit completely from the ground up to be SwiftUI driven.

Stay tuned!

Posted on 24 Mar 2020

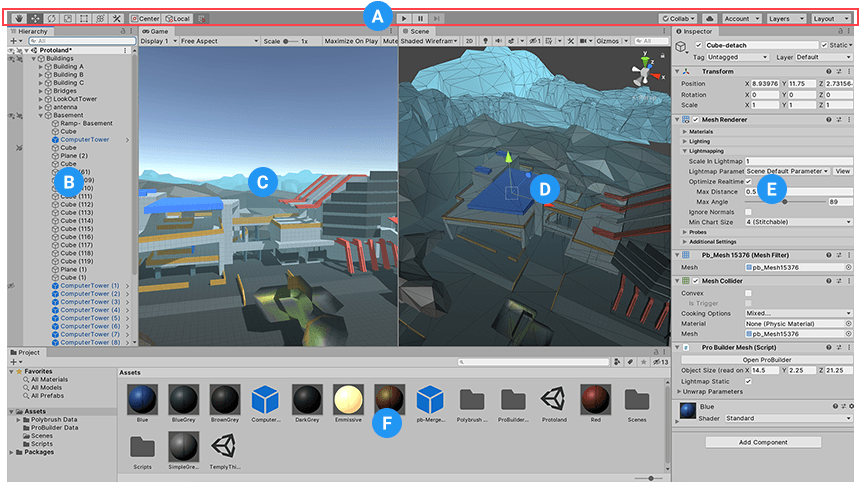

Scripting Applications with WebAssembly

The Unity3D engine features a capability where developers can edit the code for their program, hit “play” and observe the changes right away, without a visible compilation step. C# code is compiled and executed immediately inside the Unity editor in a seamless way.

This is a scenario where scripted code runs with full trust within the original application. The desired outcome is to not crash the host, be able to reload new versions of the code over and over, and not really about providing a security boundary.

This capability was built into Unity using .NET Application Domains: a code isolation technology that was originally built in .NET that allowed code to be loaded, executed and discarded after it was no longer needed.

Other developers used Application Domains as a security boundary in conjuction with other security technologies in .NET. But this combination turned out to have some holes, and Application Domains, once popular among .NET developers, fell from grace.

With .NET Core, Application domains are no longer supported, and alternative options for code-reloading have been created (dynamic loading of code can be achieved these days with AssemblyLoadContext).

While Unity was ahead of the industry in terms of code hot reloading, but other folks have used embedded runtimes to provide this sort of capability over the years, Javascript being one of the most popular ones.

Recently, I have been fascinated by WebAssembly for solving this particular scenario and solve it very well (some folks are also using WebAssembly to isolate sensitive code).

WebAssembly was popularized by the Web crowd, and it offers a number of capabilities that neither Javascript, Application Domains or other scripting languages solve very well for scripting applications.

Outside of the Web browser domain, WebAssembly checks all of the boxes in my book:

- Provides great code isolation and memory isolation

- Easily discard unused code and data

- Wide reach: in addition to being available on the Web there are runtimes suitable for almost every scenario: fast JIT compilation, optimizing compilers, static compilation and assorted interpreters. One of my favorites is Wasmer

- Custom operations can be surfaced to WebAssembly to connect the embedded code with the host.

- Many languages can target this runtime. C, C++, C#, F#, Go, Rust and Swift among others.

WebAssembly is low-level enough that it does not come with a garbage collector, which means that it will not pause to garbage collect your code like .NET/Mono or JavaScript would. That depends entirely on the language that you run inside WebAssembly. If you run C, Rust or Swift code, there would be no time taken by a garbage collector, but if you run .NET or Go code there would be.

Going back to the Unity scenario: the fascinating feature for me, is that IDEs/Editors/Tools could leverage WebAssembly to host their favorite language for scripting during the development stage, but for the final build of a product (like Unity, Godot, Rhino3D, Unreal Engine and really any other application that offers scripting capabilities) they could bundle the native code without having to take a WebAssembly dependency.

For the sake of the argument, imagine the Godot game engine. Today Godot has support for GodotScript and .NET. But it could be extended to support for Swift for scripting, and use WebAssembly during development to hot-reload the code, but generate Swift code directly for the final build of a game.

The reason I listed the game engines here is that users of those products are as happy with the garbage collector taking some time to tidy up your heap as they are with a parent calling them to dinner just as they are swarming an enemy base during a 2-hour campaign.

WebAssembly is an incredibly exciting space, and every day it seems like it opens possibilities that we could only dream of before.

Posted on 02 Mar 2020

Blog: Revisting the gui.cs framework

12 years ago, I wrote a small UI Library to build console applications in Unix using C#. I enjoyed writing a blog post that hyped this tiny library as a platform for Rich Internet Applications (“RIA”). The young among you might not know this, but back in 2010, “RIA” platforms were all the rage, like Bitcoin was two years ago.

The blog post was written in a tongue-in-cheek style, but linked to actual screenshots of this toy library, which revealed the joke:

This was the day that I realized that some folks did not read the whole blog post, nor clicked on the screenshot links, as I received three pieces of email about it.

The first was from an executive at Adobe asking why we were competing, rather than partnering on this RIA framework. Back in 2010, Adobe was famous for building the Flash and Flex platforms, two of the leading RIA systems in the industry. The second was from a journalist trying to find out more details about this new web framework, he was interested in getting on the phone to discuss the details of the announcement, and the third piece was from an industry analyst that wanted to understand what this announcement did for the strategic placement of my employer in their five-dimensional industry tracking mega-deltoid.

This tiny library was part of my curses binding for Mono in a time where I dreamed of writing and bringing a complete terminal stack to .NET in my copious spare time. Little did I know, that I was about to run out of time, as in little less than a month, I would start Moonlight - the open source clone of Microsoft Silverlight and that would consume my time for a couple of years.

Back to the Future

While Silverlight might have died, my desire to have a UI toolkit for

console applications with .NET did not. Some fourteen months ago, I

decided to work again on gui.cs, this is a screenshot of the result:

In many ways the world had changed. You can now expect a fairly

modern version of curses to be available across all Unices and Unix

systems have proper terminfo databases installed.

Because I am a hopeless romantic, I called this new incarnation of the

UI toolkit, gui.cs. This time around, I have updated it to modern

.NET idioms, modern .NET build systems, and embraced the UIKit design

for some of the internals of the framework and Azure DevOps to run my

continuous builds and manage my releases to NuGet.

In addition, the toolkit is no longer tied to Unix, but contains

drivers for the Windows console, the .NET System.Console (a less

powerful version of the Windows console) and the ncurses library.

You can find the result in GitHub

https://github.com/migueldeicaza/gui.cs and you can install it on your

favorite operating system by installing the Terminal.Gui NuGet

package.

I have published both conceptual and API documentation for folks to get started with. Hopefully I will beat my previous record of two users.

The original layout system for gui.cs was based on absolute

positioning - not bad for a quick hack. But this time around I wanted

something simpler to use. Sadly, UIKit is not a good source of

inspiration for simple to use layout systems, so I came up with a

novel system for widget

layout,

one that I am quite fond of. This new system introduces two data

types Pos for specifying positions and Dim for specifying

dimensions.

As a developer, you assign Pos values to X, Y and Dim values

to Width and Height. The system comes with a range of ways of

specifying positions and dimensions, including referencing properties

from other views. So you can specify the layout in a way similar to

specifying formulas in a spreadsheet.

There is a one hour long presentation introducing various tools for

console programming with .NET. The section dealing just with gui.cs

starts at minute

29:28, and you

can also get a copy of the slides.

Posted on 22 Apr 2019

First Election of the .NET Foundation

Last year, I wrote about structural changes that we made to the .NET Foundation.

Out of 715 applications to become members of the foundation, 477 have been accepted.

Jon has posted the results of our first election. From Microsoft, neither Scott Hunter or myself ran for the board of directors, and only Beth Massi remains. So we went from having a majority of Microsoft employees on the board to only having Beth Massi, with six fresh directors joining: Iris Classon, Ben Adams, Jon Skeet, Phil Haack, Sara Chipps and Oren Novotny

I am stepping down very happy knowing that I achieved my main goal, to turn the .NET Foundation into a more diverse and member-driven foundation.

Congratulations and good luck .NET Board of 2019!

Posted on 29 Mar 2019

Older entries »

Blog Search

Archive

- 2024

Apr Jun - 2020

Mar Aug Sep - 2018

Jan Feb Apr May Dec - 2016

Jan Feb Jul Sep - 2014

Jan Apr May Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2012

Feb Mar Apr Aug Sep Oct Nov - 2010

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2008

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2006

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2004

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2002

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Dec

- 2022

Apr - 2019

Mar Apr - 2017

Jan Nov Dec - 2015

Jan Jul Aug Sep Oct Dec - 2013

Feb Mar Apr Jun Aug Oct - 2011

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2009

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2007

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2005

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2003

Jan Feb Mar Apr Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec - 2001

Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec